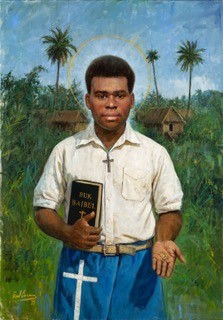

The Canonization of Blessed Peter To Rot

19 October 2025 at St. Peter’s Basilica

Life: Childhood, vocation and mission as a catechist

Peter To Rot was born in 1912 in the small village of Rakunai, Papua New Guinea, a land surrounded by tropical forests, volcanoes and islands. He was the son of Angelo Tu Puia, the village chief, and Maria La Tumul, both of whom were among the first converts to Catholicism thanks to the missionary work of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. His deeply Christian family raised their children with prayer, simplicity and zeal.

From childhood, Peter was known for his calm, generous and attentive nature. He happily participated in Church activities, accompanied his father to community meetings and showed a willingness to learn. Educated in local Catholic schools, Peter stood out not only for his good performance but also for his humility: even though he was the chief’s son, he never boasted about his origins. He had a quiet and steadfast personality.

At the age of 18, he entered the school for catechists, which operated with the direct support of the MSC Priests. There, he received solid theological and pastoral training. One of his formators described him as “a modest and obedient young man who surpassed his colleagues in dedication and zeal.” At the age of 21, already trained, he returned to his village to begin his work as a catechist.

At the age of 22, he married Paula La Varpit. The couple had three children, the last of whom was born after Peter’s martyrdom. Their family life was exemplary: they prayed together every morning and evening, lived simply, and their home was a place of welcome for the poor and sick. Peter visited the sick, taught catechism to children, organized community prayer times and helped with liturgical celebrations. He was respected and loved by the people.

Over time, his spiritual leadership grew. He had moral authority: he spoke little, but his life spoke volumes. A missionary described him as “the soul of the community.” Peter was the kind of man who united people: young and old, men and women, all saw him as someone trustworthy and close to them.

When World War II began to affect Oceania, Peter continued his service with courage. In 1942, the Japanese invaded Papua New Guinea. Foreign missionaries were arrested, and religious activities began to be monitored. The local parish priest, Fr. Karl Laufer, MSC, was taken to the prison camp in Vunapope. Before leaving, he entrusted Peter with the spiritual responsibility of the Rakunai community.

From then on, Peter officially became responsible for the faith life of the people. He visited homes, organized Sunday prayers, catechized adults and children, prepared weddings, and accompanied the sick. He recorded everything in the parish registers. He acted with such zeal and prudence that, even under military occupation, the faith remained alive and strong in the village. Peter To Rot was, in that time of silence and fear, a burning flame in the heart of the forest.

Life: Oppression, resistance and faithfulness until the end

During the first months of the Japanese occupation, there was still some tolerance for religious practice. But as the war progressed and fears of defeat grew, Japanese officials began to ban public prayers, disperse groups of worshippers, and monitor Christian leaders. Faith came to be seen as resistance. In Rakunai, Peter To Rot was at the center of this tension.

In 1944, the Japanese held a meeting with tribal chiefs from the region. They wanted to ensure political loyalty by offering cultural benefits. One of the favors granted was the legalization of traditional polygamy, which had been banned by the Church and previous governments. It was a calculated move: they hoped it would neutralize the influence of Christian catechists. Peter was one of the first to openly oppose it.

As the spiritual leader of the community, he refused to bless polygamous unions. He continued to teach catechism, promote Christian marriages, organize prayers and now, often act in secret. To protect the faithful and avoid direct confrontation, he began to hold nightly meetings in caves hidden in the woods. There, by the light of oil lamps, he read the Bible, explained the sacraments and celebrated the faith.

Peter was summoned several times by the Japanese military police. Interrogated and threatened, he responded calmly: “They want to take away our prayers. But I am your catechist. I will do my duty, even if it costs me my life.” The guards raided his home, confiscated his books, searched the meeting places, and watched his every move. Even so, he continued.

He was seen as an obstacle. The moral leadership he exercised bothered those who tried to ally themselves with the occupiers. Even without weapons, Peter was a threat to submission. He courageously defended the sanctity of marriage. He told couples: “Fidelity is a gift from God. Our people have the right to receive the whole Gospel, undiluted.” The community supported him, but everyone knew that the risk was increasing.

Despite the persecution, Peter did not hide. He continued to visit the sick, prepare the dying, and evangelize young people. He would walk up to 25 kilometers to fetch consecrated hosts in Vunapope, bringing communion to those who were dying. “God’s work is everything,” he said. His wife, Paula, worried, tried to convince him to stop. He replied: “It is my duty to die for God the Father, Son, Holy Spirit — and for my people.”

His faith was calm and determined. He prayed, fasted, and prepared himself spiritually for the worst. He knew he would be arrested. And indeed, in January 1945, soldiers came to take him away. He was taken to a dark cell, built especially for him. He was serene. When the faithful visited him, he would simply say: “Pray. Our faith cannot be bought.” The darkness of the prison would be only the beginning of his final testimony.

Life: Faithfulness until the end

Peter To Rot was already in prison. His cell was small, stuffy, and windowless. The soldiers only took him out of there from time to time to tend to the pigs. But even in this humiliating confinement, Peter remained serene. He prayed. He was grateful for the food brought by his mother and Paula, his wife. He did not complain, he did not fear. When asked about his imprisonment, he calmly said: “I am here because of marriage and faith. I will die for it.”

One day, Paula went to visit him accompanied by their two young children. She hoped to move him. Pregnant with their third child, she asked Peter to accept the Japanese request, to say that he would stop being a catechist, just to be released. Pedro, with tenderness and firmness, made the sign of the cross and replied: “I must glorify the Name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit and thus help my people.” He asked her to bring him his catechist’s cross — he wanted to keep it with him until the end.

That same day, he confided to his mother that the guards had called a Japanese doctor to give him an injection. He said, “I don’t know what that means. It’s probably a lie, because I’m not sick. Mother, hurry home and pray for me.”

At dusk, Peter washed, shaved, and put on clean clothes. He sat in front of the cell entrance and prayed. It was as if he knew. And he did know. That night, the soldiers and the doctor came. Despite efforts to hide everything, a prisoner witnessed the injection being administered. What followed was a long and painful agony. Peter suffered in silence. And, like Christ, without opening his mouth, he gave up his spirit.

The next morning, the soldiers announced, “Your catechist is dead.” Even under surveillance, a crowd rushed to his funeral. The people already venerated him as a martyr. The news of his death spread, and his story began to be told in all directions. His fidelity spoke louder than any decree. His surrender bore fruit. In his village, in the following years, priests, religious, and vocations arose — all formed in the witness of that catechist who preferred to die rather than deny his faith.

Peter To Rot is the first saint to be canonized in our Chevalier Family. And he is a layman. Married. A father. A catechist. Father Chevalier’s dream is realized in him: the Kingdom built not only by priests and religious, but by lay people who live and proclaim the love of the Heart of Jesus in the world. Peter had no pulpit, but he had faith. He had no power, but he had courage. He died without human glory, but he lives on as a seed of the living Church.

His cross as a catechist remained in his hands. And his example remained with us. May we never forget him